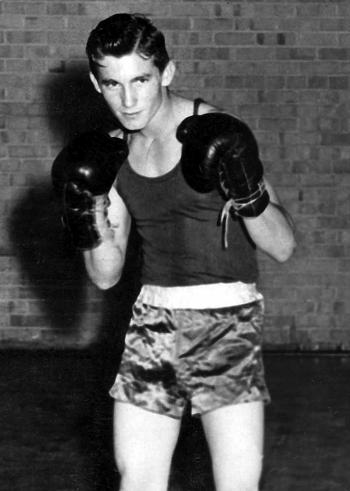

Sacred Heart's Archille "Sonny" Vidrine hits an opponent during a high school boxing match back in the 1950's. For a few decades, boxing, not football, was king in Evangeline Parish. Vidrine is one of several state champion boxers the parish produced. (Photo courtesy of Archille Vidrine)

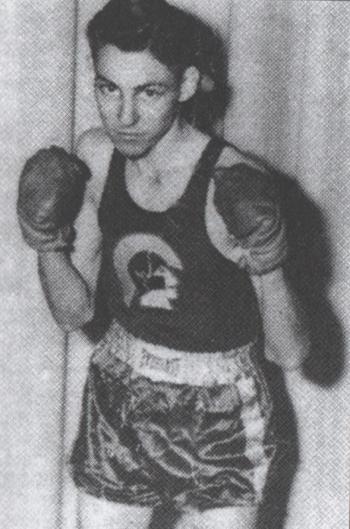

Terrona Guillory was a three-time state champion at Mamou High School. (Photo courtesy of Terrona Guillory)

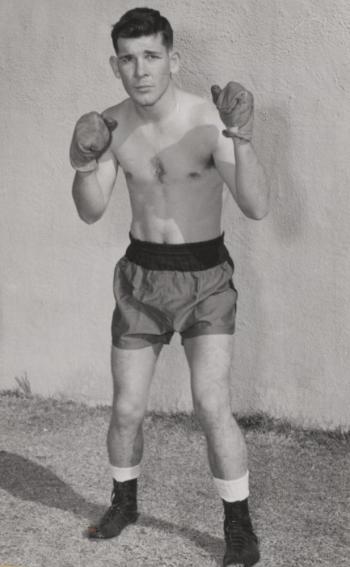

Sacred Heart's Bobby Soileau was the parish's only four-time state champion in boxing. (Photo courtesy of Bobby Soileau)

Archille "Sonny" Vidrine was a two-time state champion in boxing at Sacred Heart. (Photo courtesy of Archille Vidrine)

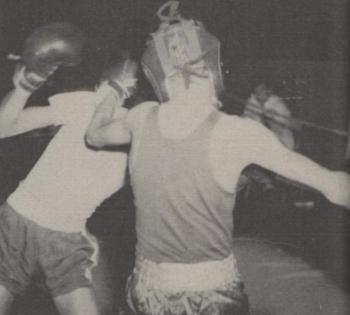

Mamou's Larry Hollier hits an opponent during a high school boxing match. Hollier was a three-time state champion. (Photo courtesy of Larry Hollier)

When boxing was king

By: RAYMOND PARTSCH III

Managing Editor

Terrona Guillory doesn’t remember the name of the young man who threw it, but the former boxer and Mamou High legend vividly recounts the jarring punch that a fellow fighter landed on him nearly 60 years ago.

“I don’t remember the guy’s name but he was from around Grand Prairie,” Guillory said. “The team we were fighting that night didn’t have anyone for me to fight in my weight class so they set up an exhibition with this guy who was 15 pounds heavier than I was.

“That first round that guy came out and hit me with the hardest punches I ever took. He hit me and I would see stars. I made it through the first round and in the second I was able to knock him out. I was glad I did.”

Like dozens of others, Guillory was part of the golden age of high school boxing in Evangeline Parish and Louisiana, an era when two teenage boys faced off in the ring was considered the king of all sporting events -- even more so than football.

The opening bell

Boxing had been around the state and the parish for decades, with small gyms springing up across the state. The sport as a high school event didn’t take off until 1931 when the Louisiana High School Boxing Tournament, which was the brainchild of Lt. Francis G. Brink, was approved and held at the LSU Gym Armory. Two years later the event would become sanctioned by the Louisiana High School Athletic Association.

In state-sanctioned matches, boxers would compete for three rounds. Those 120 pounds or less would go a minute and a half while those 120 pounds and larger would go a full two minutes in each round.

The high school boxing season would usually run between October through March and schools would take part in anywhere between 8-12 fights, before the state tournament.

Pine Prairie High School was the first parish school to compete at the state tournament, including the first two in 1931-32. Pine Prairie was one of only 20 schools to take part in the tournament that first year. The Panthers had some success in the ring as Fred O’Banion lost to Chester Carville of Catholic-Baton Rouge in the 135-pound title bout at the 1932 state tournament.

The parish’s first state champion was Dean Harrell of Ville Platte High, who won the 165-pound title in 1938.

After not having a tournament for three years due to World War II, boxing returned in 1946 and championship fighters began to spring up throughout the parish. The late Dr. Dowell Fontenot of Vidrine High took home the 98-pound title in 1946 and then claimed the 105-pound crown the following year. Fontenot would later win back-to-back national titles at McNeese State.

That same year Donald Stephenson became the first Sacred Heart boxer to win a state title as he took home the 1947 145-pound crown. Stephenson would also win the 155-pound title in 1949.

Ville Platte High’s Cecil Vidrine lost to Val Myers of Lafayette that same year in the 135-pound division.

That initial post-war success helped spur interest for the next generation of parish fighters like Larry Hollier and Bobby Soileau.

“The sport of boxing was one of the most popular in the state,” Hollier said. “It may be hard to believe but it was even more popular than football. It was a sport that everyone enjoyed in Evangeline Parish, St. Landry Parish and all across Louisiana.”

“The kids at Sacred Heart started young like I did,” Soileau said. “When I was boxing at Sacred Heart we had fifth- and sixth-graders that were training. That is just what we did.”

An atmosphere like

none other

High school boxing bouts were held in rings that were set up in school auditoriums or gyms. These matches became the in-vogue sporting event to witness in Evangeline Parish and throughout the state. A boxing match would attract anywhere between 1,000 to 3,000 people.

“In the school’s gym people would be standing shoulder to shoulder,” Guillory remembered. “The floor would be filled with chairs, the bleachers were full. Clouds of cigarette smoke filled the air. It was really packed.”

“At Vidrine there would be 700 reserved seats and they were always full,” Hollier said. “The place would be so filled that people would be walking around the gym trying to get information on who was winning the fight because they couldn’t see.”

That fervor only increased at larger events. An estimated 2,500 watched Ville Platte High’s Leland Fontenot defeat Oak Grove’s James Posey at the 1948 Camellia Bowl Sports Classic in Lafayette. After starting at the LSU Gym Armory, the state tournament would later move to the John Parker Coliseum which had a capacity of 12,000. The tournament later was moved in 1950 to the 5,500-seat capacity of Blackham Coliseum at Southwestern Louisiana Institute of Liberal and Technical Learning (SLI), now known as University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

“It was tremendous,” Hollier said. “To get to the ring we had to be escorted by police. You felt like a pro that you saw on television.”

Like his fellow competitors, for two-time state champion Archille “Sonny” Vidrine of Sacred Heart, stepping between those ropes was nothing to joke about.

“It was serious,” Vidrine said. “You took it very serious. If you got beat by somebody you had to do a lot of fighting to catch back up.”

Putting on the gloves

Soileau’s initial interest in boxing stemmed from having to wait on his father to pick him up after school.

“I would go to gym and watch the big boys practice boxing,” Soileau remembered. “I decided one day that I would punch the bag. The coach at the gym asked who I was and told me if I wanted to be a boxer than I needed to come to practice.

“So I told my dad one day that he could still pick me up but that I would still be practicing at the gym. He told me that if I was still practicing then I would be walking home. After I won my first fight I didn’t mind walking home.”

While Soileau stumbled onto the sport, Guillory became involved with the sport as way to deal with his penchant for fighting in school.

“When I was in school I would get into a lot of scraps,” Guillory said. “I hated bullies. One day when I was about 11 years old I got into three fights. The principal and my classroom teacher decided if I liked to fight so much that they would get me where I could do it.

“So one afternoon they brought me to the high school gym, they said they would like me to try out. It was the end of the boxing season and coach had me fight an older boy who was on the team. I got into the ring and I beat the hell out of him. The next year the coach visited me at the school and from there I was on the team.”

Vidrine, who won his first state title in sixth grade, said it was rare to find a championship-caliber fighter who started off as someone who wasn’t worth a flip.

“Boxing is a natural sport,” said Vidrine, whose older brother and father both boxed. “Very rarely did you ever find someone who wasn’t good at it to begin with then become a real good fighter.”

The exception to that rule was Hollier.

For a skinny kid like Hollier, his passion helped guide him through early rough years in the sport. He first tried out for the Mamou boxing team in sixth grade but didn’t make the team, made the team the following year but didn’t win his first fight until he was in the eighth grade.

“I was always amazed by boxing,” Hollier said. “I lived a block from the school. I would go and watch them train all the time. I loved the sport. It is one-on-one. I was a skinny little kid but I continued to pursue it.”

The dynasty &

the Brink winner

Vidrine High and Sacred Heart each produced fighters that have been inducted to the Louisiana High School Boxing Hall of Fame. No other Evangeline Parish school though had as much success in the ring than the Mamou Green Demons.

During the seven seasons between 1952-58, Mamou had boxers win individual state titles 17 times, had a state champion crowned every year except for 1957, produced a pair of three-time state champions in Hollier and Guillory and took home two overall team state titles in 1952 (coached by George Johns) and then again in 1955 (coached by T.J. Viator).

So why was the small Cajun town so good at producing championship boxers?

“The whole thing to us winning was our conditioning,” said Hollier, who won titles in 1952, 53 and 55. “We could see you in the corner and see that you weren’t winded out. I don’t care how good you are, if you are not conditioned then you will lose.”

Ironically, the conditions of the gyms at Mamou and other schools almost forced Guillory to quit.

“People back then didn’t know anything about allergies,” said Guillory, who won state titles in 1954, 55 and 56. “When I started off my first season everything was going good but the second match we had at the school, by the second round I was pooped out. I couldn’t catch my breath. A handful of my fights had to be stopped in the second or third rounds. No one could figure out why I didn’t have any problems in practice. I could spar for 12 rounds and not once get winded. I was just going to quit but coach persuaded me to stay on.

“Then I went to state at LSU in seventh or eighth grade and there was no smoking allowed and I didn’t have any problems with my breathing. I found out years later that the cigarette smoke was getting to me. That I was allergic.”

Despite that health challenge, Guillory would go on to win three state titles, finish as runner-up twice and is often discussed as one of the parish’s greatest boxers.

But there is only one fighter from the parish that can boast of having four titles, and that distinction belongs to Solieau.

Soileau, born George Willard Soileau, began boxing at Sacred Heart in the eighth grade and won his first title that same year taking the 90-pound weight class crown in 1950. He would proceed to take the 100-pound crown in 1951, the 110-pound title in 1952 and the 125-pound championship in 1954. His lone loss at state came in 1953 during the 115-pound finals against Bruce Boudreaux from state powerhouse Plaquemine, which is still regarded as one of the greatest fights in the state’s storied history.

In addition to being the only boxer from the parish to be crowned a state champion four times, Soileau is also the only one to earn the Francis G. Brink Trophy, which was given each year to the state’s best boxer.

“He was just such a good fighter,” Ville Platte High fighter Glenn Fontenot said. “I think my record in high school was like 60-5. The only year I reached the state tournament I fought Bobby in the opening match. He beat me by TKO. He took care of me. He beat everybody to the punch.”

Yet, Soileau, well-known for his left jab, doesn’t dwell on those championships. Instead he gives all the credit to his Hall of Fame coach, Jack Reed.

“He was a truly great coach,” Soileau said. “I had a girlfriend in high school that lived next door to him. When I visited my girlfriend he would come knock on the door and say it was almost 10 o’clock and that is was time to get home.”

The fight of century

There were plenty of memorable fights between boxers from inside the parish.

Hollier fought and defeated his former teammate Kern Ardoin, who had transferred back to Vidrine High, at the state tournament in 1955.

Glenn Fontenot fondly remembers a friendly but brutal bout he had with Gilbert Deshotel from Vidrine High.

“It was a lot of fun,” Fontenot said. “He knocked me out of the ring. So they pushed me back in and when I got back in there I knocked him down. It is something you ain’t going to forget. I still love boxing.”

Sometimes the fights weren’t even sanctioned bouts.

“They used to spar all the time,” Judge John Saunders said. “Both Bobby (Soileau) and Archille (Vidrine) have told me this story. Bobby was very fast but he dropped his guard one time and Archille put him on the canvas. Coach said ‘Soileau you are going to run for letting that little boy hit you.’ He said, ‘Coach I will run all you want but give me two minutes with him.’”

Like Vidrine, Guillory had more than his share of brawling bouts. He clashed with Gerard Fontenot from Vidrine High a handful of times, including breaking his nose once. Guillory cites his sparring partner Daniel Hoffpauir as the toughest he ever faced.

“I could have hit him with the corner post of the ring and he would still be standing.”

There was one fight, though, that is considered the greatest fight between two in-parish boxers, and that was the Guillory-Vidrine fight for the 1957 120-pound state championship.

“The fight between Archille and Terrona is probably the most famous Evangeline Parish match ever,” Saunders said. “Both were sluggers and that year they were the same weight. I wasn’t there but I have heard about the fight so many times over the years. I was told that money was thrown into the ring. It was the fight of the century.”

The first round saw each fighter go fist-to-fist for three minutes. Then in the second round, an unexpected KO occurred.

“He was the king,” Vidrine said. ‘Nobody could stay in the ring with him. He would knock everybody out. He was a real tough fighter. After the round I said an expletive and told my coach that he could hit. I knew that I needed to finish it the next round so I knocked him out instead.”

“When I fought Archille they had to stop the fight in the second round,” Guillory said. “I hit him in the face and his eyes rolled back a little bit in his head. I thought I hear the ref say break and I leaned back and began to put my hands down. Archille hit me in the side with an uppercut and I had the wind knocked out of me. I never was able to get my breath back.”

After the final bell

After a initiative by some of the state’s private Catholic schools, the LHSAA decided to drop boxing as an officially sanctioned sport in 1958. At the same time colleges and universities decided to follow suit and eliminate their boxing programs all together.

Fontenot, whose uncle also boxed at Ville Platte High, experienced that disappointment earlier than his counterparts. After boxing for three years, Ville Platte High, pressured by the PTA, decided to disband the boxing program before Fontenot’s senior season following the 1953 season.

“All of us were disappointed,” said Fontenot, who later won a Gold Gloves tournament in Lake Charles in 1954. “It just faded away.”

Soileau, who went to LSU on a boxing scholarship, was part of the Tigers’ 1956 national championship team, all of the sudden found himself without a sport.

“I had just won the national championship in college and my coach called me in one day and he said I got some bad news, we are losing boxing. LSU is going to drop boxing.”

Soileau thought about possibly going pro but he had injured his shoulder during the Olympic Trials, a pinched nerve that still bothers him to this day. He left LSU to take an assistant coaching job at McKewin High in Jackson, Louisiana before returning home to coach football at his alma mater.

Soileau would win 154 games, win the 1967 state title, finish as state runner-up in 1972 and was a two-time Coach of the Year.

“Boxing made me a better person and it made a better coach,” Soileau said.

Hollier, who joined the U.S. Army in 1955, was for a short while on the boxing team for the 11th Airborne, and once had the greatest boxer of all-time Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, open the ropes for him during a tournament in Louisville.

Guillory, who had been offered a boxing scholarship to LSU, meanwhile nearly joined the FBI in 1958 but ultimately returned home and became a roustabout in the oil field to help take care of his family.

Vidrine had success as a boxer in the Armed Forces, as he would be crowned All-Army champion. After joining the U.S. Army in 1960, Vidrine went right into boxing after being stationed in Okinawa, Japan.

“When I went to the base to do my job and I tried out for boxing,” said Vidrine, who estimates he boxed in more than 60 matches in a three-year span. “My last two years I didn’t wear my Army uniform unless we traveled and boy did we travel. We went to Korea, the Phillippines and China. The only place we didn’t fight was in Bangkok, Thailand because they would kick and punch at the same time.”

After his time was up, Vidrine no longer wanted to pursue boxing.

“I had enough,” Vidrine said. “I was tired of living boxing. In the military you ate, drank and slept boxing.”

In the decades since then, the parish’s boxing history began to fade but those who put on the gloves kept the sport’s memory alive by having semiannual reunions starting in the late 1970’s. The reunions were a great way of catching up and reminiscing about the old days but each reunion saw smaller attendance as those people began to die off.

In recent years, there has been an effort to preserve the history of high school boxing. Inspired by attending reunions, Don Landry penned the book “Boxing: Louisiana’s Forgotten Sport” and after two induction classes, the Louisiana High School Boxing Hall of Fame (which features seven from the parish) held its grand opening in the Iberville Museum in Plaquemine this past fall.

For those who lived the life of a high school boxer, that time spent between the ropes proved to be valuable for the decades to come.

“It meant a lot to be competitive and be better than somebody else at a particular job,” Vidrine said. “It was the thing at the time that I was the best at. I loved it.”

Added Guillory, “It gave kids confidence in themselves. You can do whatever you want to do. It teaches you how to get along with people. It makes you look at them a different way. It was the most important sport that we had around here.”

- Log in to post comments